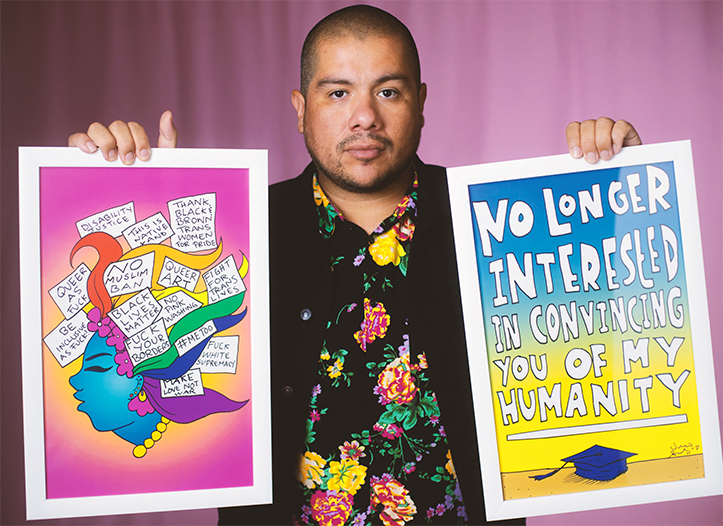

Credit: Wil Prada

As an illegal LGBT immigrant, Julio Salgado has discovered that the artistic practices he learned in school have helped him cope with sadness, pessimism, and stress. He later utilized his talent to help millions of individuals just like him raise their voices.

Julio Salgado is dressed in a flowery print shirt and a black jacket, and he is clutching two pieces of his artwork in each hand. On his left, there’s a side profile of a lady with multicolored hair, as well as messages like “Black Lives Matter“, “#MeToo“, “Make Love Not War”, and “Thank Black and Brown Trans Women for Pride”, “No Longer Interested in Convincing You of My Humanity”, says the artwork on the right, with a graduation cap at the bottom.

When Julio Salgado first heard the news, he couldn’t believe it.

In May of 2010, five people dressed in graduation gowns entered the late Senator John McCain’s office, sat on the floor, and refused to move. Tania Unzueta, Lizbeth Mateo, Yahaira Carrillo, Mohammad Abdollahi, and Ral Alcaraz linked arms and urged McCain to support the DREAM Act, granting conditional resident status and a path to permanent residency to a generation of illegal immigrants aged 12 to 35.

“When they did the sit-in in McCain’s office, they really altered the game because, up until that moment, people were speaking on our behalf, and they were fucking being jailed,” Julio Salgado adds. “I felt it was a piece of b*ss that they did it.”

Their action sparked a new surge of activism and rallies in favor of the DREAM Act, inspiring Salgado to be more daring with his paintings. It started out as a simple way for him to acknowledge the critical work that many organizers and activists were doing on the ground to elevate the voices of millions of people like him. It has evolved into a method of supporting and uplifting those who, like him, identify as both undocumented and LGBTQ.

“Four of the five persons you saw sitting down [in McCain’s office], four of them identify as LGBT,” he continues.

Salgado began drawing as a child in Ensenada, Baja California, where he grew up. He can’t recall a moment when he wasn’t painting. His artistic abilities earned him a cake in a drawing contest organized by a local radio station on the Dia del Nino celebration.

Julio Salgado’s illustration features a pink shirtless person with rainbow butterfly wings. The wording and phrases on each section of the wing are distinct. “Migrant queerness” and “Love, family, togetherness, peace” are written in English on the right wing. “Joteria Migrante” and “Amor, Familia, Unidad, Paz” are written on the left wing in Spanish.

Salgado and his family traveled to Los Angeles in 1995. Due to his sister’s health issues, his parents decided to keep the family in California and overstay their visas. He and his family relocated to Long Beach permanently after she was diagnosed with a life-threatening renal condition.

To help him interact and connect with others in his new circumstances, Salgado resorted to his art.

“My sister became ill,” he adds, “and she ended up requiring a kidney transplant, so my mother donated one of her kidneys to her.” When your child is sick, you don’t worry about the political climate, which was anti-immigrant at the time.”

To help him interact and connect with others in his new circumstances, Salgado resorted to his art.

Julio Salado’s illustration shows a group of people of color standing side by side across a boundary. “We exist!” it says above them, despite the anguish, tears, criminalization, erasure, and anguish. The words “Bigger than any border” are painted on the border.

“I was always drawing in class,” he recalls, “and other kids would be like, ‘dang foo, you know how to draw?'” Is it possible for you to draw my name in stylish letters? ‘Could you please sketch me?’ So, from an early age, I began to use art to gain friends, and I understood that if you are creative, people would like you. It was a means for me to make friends and communicate.”

Salgado aspired to study painting in New York after high school and become the Mexican Andy Warhol. His hopes were shattered when he discovered that being an unauthorized citizen barred him from qualifying for financial help. His parents, like him, were living paycheck to paycheck.

As he considered his future step, Salgado stayed in Long Beach and worked different lowly jobs such as dishwasher and construction worker. The World Trade Center skyscrapers in New York City were attacked months later on 9/11, and the anti-immigrant fervor in California in 1995 paled in contrast to the countrywide venom and hatred directed at anybody regarded as foreign and un-American in the aftermath.

During this period, Salgado resorted to his art to help him cope with all of the changes and circumstances. He had private sketchbooks and notebooks in which he sketched and wrote. These helped him deal with the melancholy and loneliness he was experiencing at the time.

I have no control over many things, but I do have power over my work.

“Of course, I look back and think I was a huge drama queen,” Salgado laughs, “but you always feel alone.” You wonder whether you’re the only undocumented student seeking to attend college. I was working on a construction site, cleaning dishes, and thinking to myself, “This can’t be it.” That came from my mother, and it came from my To Chicho, who desired more… I wasn’t even talking about millions of dollars! I only want to be able to attend school and learn. It was stressful to have to persuade others that you’re worth those things, but it got me through it.”

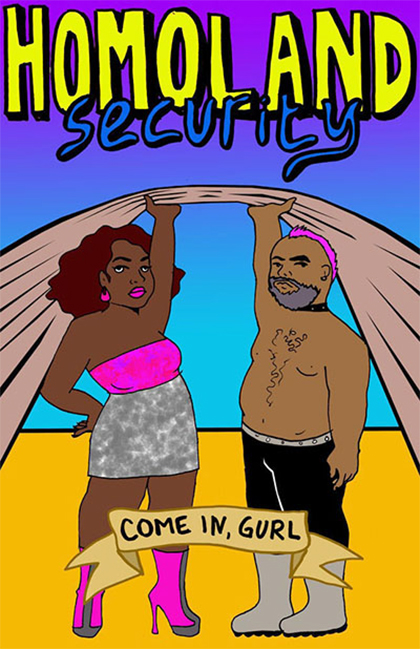

Julio Salgado’s illustration portrays two persons of color raising a curtain. “Come in, gurl,” says a banner draped over their knees. “Homoland security” is written above them in large, bold characters.

“Homoland Security,” a 2013 artwork by Salgado. Source: juliosalgadoart.com

He explains, “It was my method of dealing with a lot of these things.” “I usually say that though I don’t have control over a lot of things, I do have control over my art. As a result, it was a means for me to exert control over how I felt. As artists, I constantly remark that we are fortunate to have access to this type of treatment.”

Salgado later enrolled in Long Beach City College, where he pursued his interests in art and journalism. When he signed up to make political cartoons for the school paper, it was here that he began his first professional journey into painting.

He continues, “This is a technique to mock politicians.” “Many of the things that politicians said had an impact on me, and I was turning them into art. It was basically my point of view.”

He became engrossed in the works of Aaron McGruder, the author of The Boondocks, and Lalo Alcaraz, particularly his political cartoons on California’s Prop. 187, now-defunct legislation that denied unauthorized immigrants the right to work. Immigrants access to public benefits like non-emergency health care and public education. Salgado later transferred to California State University Long Beach, which he credits with his political awakening. It was there that he met and collaborated with other undocumented students to talk about their experiences, publish zines, and host events together.

Those early days at LBCC and CSULB were the first steps towards a life of arts activism, later pushed on by the protest at McCain’s office. Soon after, activist Jorge Gutierrez urged him to create what became Salgado’s UndocuQueer series of portraits in 2012. The series consists of painted portraits of immigrants’ rights activists who are undocumented and queer. Each portrait also includes a quote by the subject. Carrillo, who sat in McCain’s office years ago, is the subject of one such portrait.

The purpose behind the series is to remind people that UndocuQueers did the bulk of the work pushing the national conversation on immigrants’ rights, planning and executing protests, and all the other unglamorous behind-the-scenes work. It’s also to expand the conversation behind the perceptions of these immigrants affected by these laws and policies.

An illustration by Julio Salgado depicts a person wearing a white t-shirt and holding a bullhorn standing in front of a hot pink background. Above them are the words, “I am UndocuQueer.” To the left of them is a quote that reads, “Coming out of the shadowy closet: Undocumented and queer, join me! – Reyna W.”

I started making those pieces for our communities to understand that if we’re talking about accepting people or creating policy that doesn’t criminalize us, we can think about other folks who are also part of our communities.

On multiple occasions, Salgado has had to educate numerous people about the diversity of people who identify/are labeled as undocumented. In one such instance, he and others traveled by bus from California to Washington D.C. for a massive march on the capitol.

“A lot of them were faith-based groups,” recalls Salgado. “There were some immigrants who were very homophobic that would say homophobic things and, like, how do you navigate those spaces? You have to educate people, which I don’t have a problem with that. Working in kitchens with a lot of immigrant men and their machismo, you learn how to use humor.”

“That’s why I started making those pieces,” he continues. “It was for our communities to understand that if we’re talking about accepting people or creating policy that doesn’t criminalize us, we can think about other folks who are also part of our communities.”

“It was the same thing in queer spaces,” Salgado adds, recalling a similar incident that occurred during a Pride event in Long Beach nearly ten years ago when the conversations around the LGBTQ community centered on gay marriage and military enrollment.

“There was this Wells Fargo float at Pride, and I was booing them,” he explains. “Some gays around me were like, ‘This is not the time to be booing.’ And I was like, ‘Y’all know that Wells Fargo benefits from the incarceration, or invests in the incarceration, of immigrants.’ I was trying to have this conversation with white gays, and they were like, ‘yeah, but this is a time to celebrate. It’s not a time to be booing people.’ In my head, I’m like; Pride started as a riot! And all of a sudden, you’re being told that that part of you needs to be okay with the gay party?”

Since producing the UndocuQueer series in 2012, Salgado has continued to paint portraits in various styles. The subject matter still relates to a life lived as undocumented and queer but has shifted from a demand to acknowledge one’s existence to simply existing on one’s own terms. For example, he created a piece that features a student dressed in a graduation cap and gown in that same year, flipping the viewer off with one hand. The text above them reads, “I’d Rather Die Undocumented Than Die For Your Acceptance.” Another piece in 2017 features a graduation cap sitting on the ground. The text above it states, “No Longer Interested In Convincing You Of My Humanity.”

“At this point where I’m at in my life, I want to make art that is not just focusing on me being sad all the time,” says Salgado. “It’s time to move on. Let’s make art that gets into all the things that we are as immigrants, as queer people, as people of color. One book, one film, one piece of art is not going to cover it all. We need a lot of voices.”

To that end, Salgado launched The Disruptors Fellowship via the Center for Cultural Power in Oakland. The fellowship is designed to support “emerging television writers of color who identify as transgender, non-binary, disabled or undocumented/formerly undocumented” in Los Angeles by providing them with mentorship, master classes, and a monthly stipend to support their work to disrupt the status quo in Hollywood. This year, fellowship winners will learn from Linda Yvette Chávez, co-creator of ‘Gentefied,’ and Josh Siegal, a writer on ’30 Rock,’ who will teach a master class.

“I’ve been really lucky to have been able to connect with people that are working in Hollywood,” says Salgado. “My art has been used in a couple of TV shows, and that’s nice, but let’s create networks, let’s create systems that get us there because I wouldn’t be here without the mentorship of other folks.”

Salgado is also the resident illustrator for Cumbiatón, an intergenerational dance party founded by Zacil Pech and Norma Fajardo in 2017, created to form an inclusive and safe space for undocumented and queer people of color. He sees it as a fun way to create a positive environment for marginalized people while also utilizing the space to educate others.

“When I was in college, and I was introduced to the Riot Girl movement using music, using punk shows to educate folks, I was influenced by that,” explains Salgado. “We need to do that in our communities ourselves. I think it’s great, and it’s messy, and I love it!”

Featured image, photo credit: Wil Prada