SOURCE: SprayPlanet

A History of Graffiti – The 60’s and ’70s

Given the monumental influence graffiti art has had on our popular culture, from music, film, and television to fine art, toys, and clothing, it’s easy to forget the form’s humble roots and remarkable evolution — how what started as a way for bored kids to pass the time grew into a movement larger than anyone could possibly have imagined.

Indeed, long before the giant murals, fashion runways, larger-than-life art shows and unlikely street art millionaires, modern graffiti art got its start in the belly of a Philadelphia juvenile corrections facility, with a single word scrawled in small caps across a cell wall: CORNBREAD.

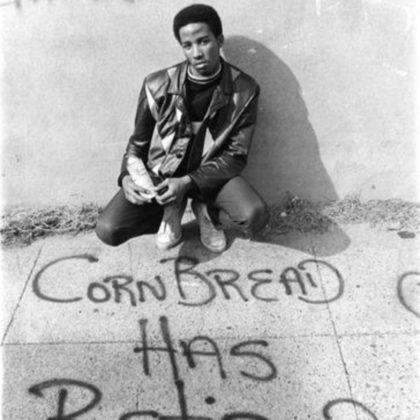

Cornbread & The Unlikely Beginnings of Modern Graffiti Art

In 1965, Darryl “Cornbread” McCray, now widely considered the world’s first modern graffiti artist, was a 12-year-old troublemaker housed at Philadelphia’s Youth Development Center (YDC).

As you may have guessed, McCray loved cornbread. He loved it so much, in fact, that the YDC’s cooks nicknamed him “Cornbread” when he would not stop pestering them to make him the cornmeal quick bread he’d grown up eating with his grandmother.

Instantly taken with his new name, Cornbread felt compelled to share it with the other boys. Rather than take part in the drug use and violence that ran rampant at the YDC, Cornbread passed the time by adding his unique signature to the facility’s walls, which, until then, had been covered exclusively in gang names and symbols.

Cornbread spent day and night hunting for fresh spots, scrawling his newly-acquired moniker on nearly every surface in the YDC. He tagged the visitor hall, chow hall, church, and bathrooms, writing “Cornbread” so obsessively that social workers thought he might be suffering from a mental disorder.

Upon his release, Cornbread doubled down on the work he’d started in juvie. He took to the streets of Philadelphia, joining forces with friends (and future graffiti legends) like Cool Earl and Kool Klepto Kid to tag walls across the city.

He even used the blank brick canvases of North Philadelphia to win over his junior high crush, writing “Cornbread Loves Cynthia” all over the girl’s neighborhood and along the bus route she took to school.

The plan worked, and Cornbread’s enigmatic tag soon inspired others, the city’s walls growing dense with various names and numbers, each writer trying to snag their share of the glory.

When a local paper mistakenly reported that Cornbread had been killed in a gang shooting, the prideful young writer was determined to prove the legend was still alive. “I knew it was up to me to bring my name back to life,” he told Philadelphia Weekly.

In a bold display that would forever cement his status as an icon of 1960’s graffiti, Cornbread snuck into the Philadelphia Zoo, hopped a fence, and painted “Cornbread Lives” on both sides of an elephant.

The stunt landed him in jail. But even there, Cornbread claims, his reputation followed him. In Wall Writers: Graffiti in its Innocence, Roger Gastman’s seminal documentary on the pioneers of 1960’s graffiti, Cornbread relates how the jail’s guards would ask for his autograph, noting with pride: “My name rang like Jesus Christ.”

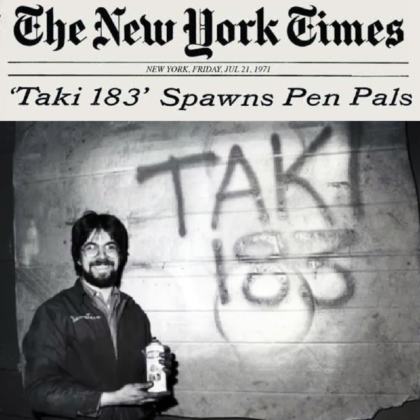

Taki 183, The King of Late 1960’s Graffiti

Around the same time that Cornbread and the Philadelphia crews were busy spraying elephants and trying to out-tag one another, a parallel 1960’s graffiti movement was developing in New York City.

It was a time when, as Henry Chalfant and Sacha Jenkins put it in their book, Training Days: The Subway Artists Then and Now, “New York didn’t have much, [and] the kids had to figure out what to do with themselves.”

One of those kids was Taki 183, a self-described bored teenager from Washington Heights, a Greek neighborhood just north of Harlem, who created his now-iconic tag in 1969 by combining “Taki,” a diminutive form of his Greek name, Demetrius, and “183,” his street number.

Taki was not the first writer to combine name and number in his tag (he cites Julio 204, who stuck mostly to his own neighborhood, as a major inspiration), but as Complex noted in an article on the 50 greatest NYC graffiti artists, Taki was “the first to turn [tagging] into a 24 hour a day job.”

Armed with magic markers and spray cans, having cut a hole in his jacket that allowed him to hide his hand as he worked, Taki tagged walls, lampposts, hydrants, and subway cars across New York City, carefully choosing the spots he thought were most likely to be noticed.

Like Cornbread before him, Taki soon became obsessed. “I liked the feeling of getting my name up, and I liked the idea of getting away with it,” he told Street Art NYC. “Once I started, I couldn’t stop.”

Taki’s job as a bike messenger took him up and down the city and into the high-end neighborhoods of New York’s Upper East Side, so that soon, as Taki put it in an interview years later: “You could walk 40 blocks and see my name on every pole.”

Taki’s quest to conquer the city caught the attention of a reporter at the New York Times, and a 1971 profile instantly catapulted Taki to legendary status among his peers in the early 1970’s graffiti scene.

“I don’t feel like a celebrity normally,” he told the paper, “but the guys make me feel like one when they introduce me…‘This is him,’ they say.”

The first New Yorker to become famous by writing graffiti, Taki would inspire a generation of writers from across the city, just as Cornbread had in Philadelphia. It’s appropriate, then, that the two men came together at MOCA Los Angeles some 40 years later to sign their installations at Roger Gastman’s Art in the Streets exhibit and celebrate how far the movement they started had come.

Tagging for Glory: The Pioneers of Early 1970’s Graffiti

As these stories demonstrate, the early graffiti writers of New York and Philadelphia had a lot in common. They were bold, creative, and dedicated, yes, but also young and mostly poor, with limited choices of how and where to spend their free time.

As Bama, a writer from the Bronx puts it in Gastman’s film: “You could be on the basketball team, you could be in a gang, or you could go out here and write on the walls.”

It makes sense, then, that graffiti took on a special meaning for these early writers. As sociologist Gregory Snyder notes in his book, Graffiti Lives: Beyond the Tag in New York’s Urban Underground, tagging allowed these young men and women the opportunity “to get fame and respect for their deeds,” rewards which, in any other part of their lives, were totally elusive.

In this sense, Snyder argues that “in its purest form, graffiti is a democratic art form that revels in the American Dream.”

This quest for glory meant that graffiti was “frequently thicker in tourist areas like SoHo than in poorer, less-trafficked locales, showing that for most writers having their work seen [was] more important than anything else.”

It also meant that, in the early 1970’s graffiti, legibility — not style — was of prime importance. After all, as Jon Naar notes in Gastman’s film: “They called themselves writers, not artists.”

Driven by the “competitive nature of urban life,” these writers used whatever they could find — from shoe polish to industrial markers — to spread their tags across the city, eventually painting subway trains at night to ensure their work made its way (very efficiently) across New York’s 5 boroughs, taking their name “all-city” in the process.

One writer, MICO, condenses the early history of graffiti into a few simple lines: “It began in different neighborhoods. But we all had one thing in common: We wanted to be famous.”

Bubbles, Softies, and Subways: The Stylish Mid-70’s & Beyond

In the mid-1970s, with tags going up on walls across New York City and subway cars surfacing each morning covered in elaborate new pieces, graffiti art became a political target.

Though many in the public appreciated the burgeoning form, New York City mayors John Lindsay and Edward Koch vowed to crack down on what they saw as a symptom of a larger “urban problem” in the city. Cleaning up the graffiti became a way to prove that, as Snyder puts it, “the politicians were back in control.”

Such efforts posed a major threat to the 1970’s graffiti writers, as subway cars had become essential tools for ferrying new work across the city and building reputations, with writer C.A.T. 87 describing the city’s trains and buses as “international routes.”

The writers soon fought back with waves of protest graffiti. Using subway system maps and shared intelligence, they warned each other about which spots were safe and which were too hot, beginning what MICO called, in a New York Magazine history of graffiti, a “guerrilla war” that eventually drained the city’s resources.

Such circumstances also fostered a new climate of creative innovation. As journalist and music critic Jeff Chang explained: “The MTA’s attempts to whitewash the trains only further intensified the process of stylistic change, because there were many more potential targets, and they’re all clean canvases.”

As a result, Snyder writes, 1970’s graffiti soon “progressed from scribbled signatures done with magic markers to elaborate masterpieces done with multiple aerosol colors in the dark of night,” legibility taking a backseat to style and artistic originality.

Writers began experimenting with new lettering styles and flourishes, embellishing their tags with stars, flowers, crowns, and eyeballs, simple tags evolving into what Raw Vision’s John Maizels called “hieroglyphical calligraphic abstraction.”

Among the iconic writers of this period were Superkool 223, who discovered that a larger spray nozzle allowed him to fill in letters more quickly and who is credited with graffiti art’s first masterpiece; Tracy 168, whose work appears in the opening credits of John Travolta’s classic sitcom Welcome Back, Kotter; and Phase 2, who is aptly named given his major role in ushering in a new era in the history of graffiti art.

A native of the Bronx, Phase 2 (born Lonny Wood) created the now-iconic bubble style of aerosol writing — thick, marshmallow-like letters, also called “softies,” that would feature in so many of the period’s pieces. A relentless innovator, Phase 2 also pioneered many other techniques seen in graffiti before 1980, including interlocking type, arrow-tipped letters, and the use of icons like spikes, eyes, and stars.

Given his legendary status in the development of graffiti before 1980, it’s no surprise that Phase 2 would also go on to play a significant role in the following decades, as graffiti art became increasingly connected with the emerging hip-hop scene.

These developments in 1970’s graffiti set the stage for such new forms as the intricate “Wildstyle” brand of writing, one unique style which helped transition graffiti from simple words scribbled on lamposts to epic artworks admired around the world.

As we’ve seen, however, “wild style” was not only a new way to tag walls and subway trains; for the pioneers of modern graffiti art it was also, as Tracy 168 put it, “the way we lived.”